Massacre of Lagganmore

By Patrick H. Gillies, M.B., F.S.A. Scot.

[This article was originally printed in the Journal of the Clan Campbell Society (North America) Vol. 37 No. 3 Summer 2010 and may not be re-published in whole or in part without the written permission of the various authors and the Clan Campbell Society (North America).]

Introduction: This article is a reprint from a section of Patrick Hunter Gillies, M.B., F.S.A. Scot’s 1909 book Netherlorn Argyllshire and its Neighbourhood. The style is Celtic-Romance, straight out of the 19th century when James Macpherson’s “Ossian” was still popular. Some of the longer paragraphs have been broken up for ease of reading; otherwise, this passage, including the quote from “Ossian,” is intact.

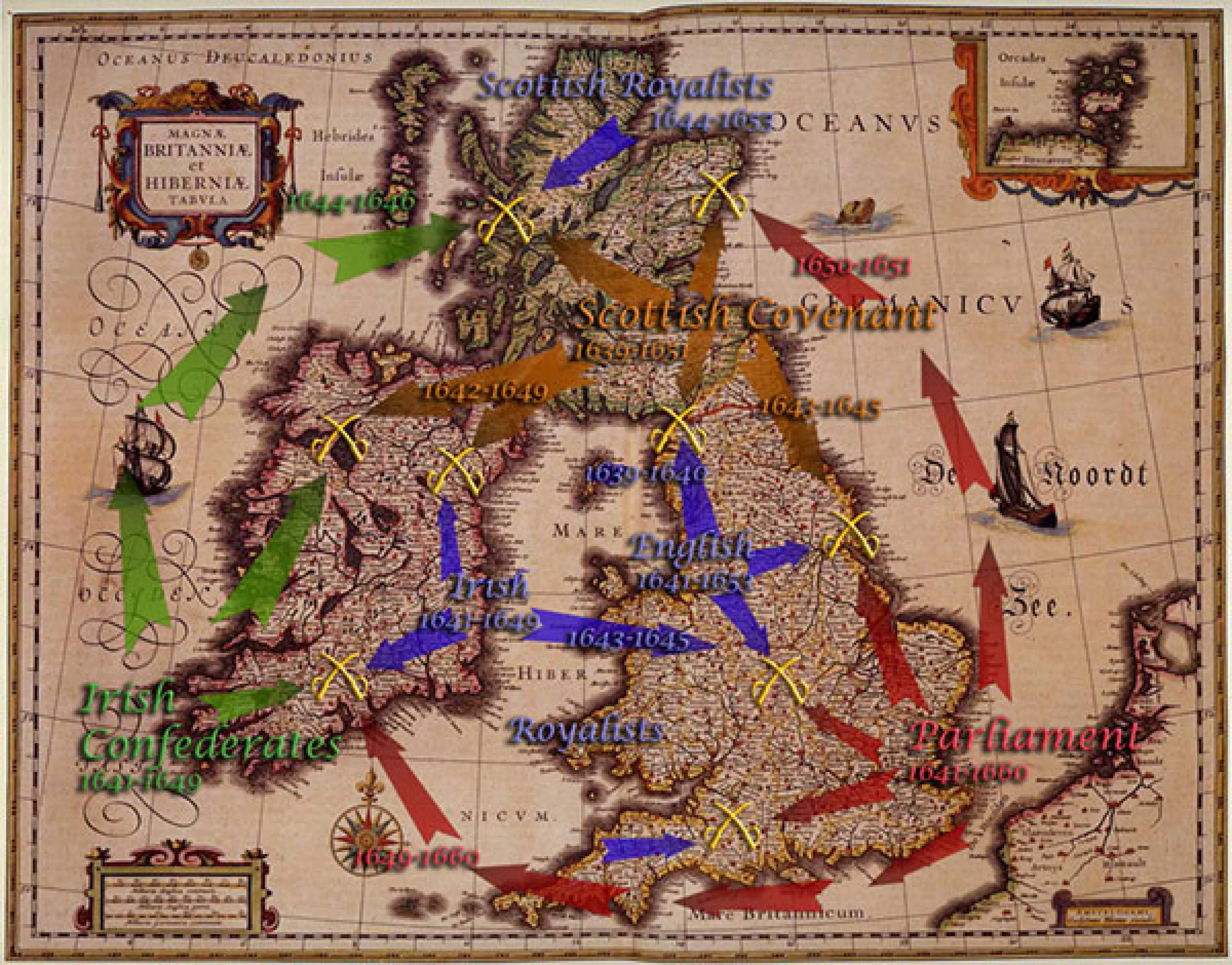

England and Scotland had become a united kingdom with the Union of the Crowns in 1603 (forerunner of the present UK), and Ireland was a colonized protectorate, all under the reign of King James VI of Scotland and First of England, who had been succeeded by his son King Charles I in 1625. The background to the civil wars of the 1640s is overly complex, sufficient to say that the involvement of the English Parliament coupled with the disaffected religious factions in the three countries would eventually end with the execution of the king and the creation of a Commonwealth presided over by Oliver Cromwell and his victorious Parliamentarian army. Presbyterian Scotland followed the National Covenant of 1638 against the king’s introduction of an Episcopalian prayer-book, supported by many of the nobility including Archibald Campbell, Marquess of Argyll.

Covenanter-turned-Royalist James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, gathered many of the Roman Catholic and Episcopalian Highlanders to fight for Charles, aided by Irish soldiers under Alasdair MacColla, (“Alexander, son of Coll”, referred to below as Alexander MacDonald). As Gillies picks up the story, it is the Spring of 1646. Cromwell is ascendant but not in power yet. Montrose is defeated. The King’s days are numbered. MacColla has turned to ravage Argyll.

“Is the remembrance of battles always pleasant to the soul? Do not we behold with joy the place where our fathers feasted? But our eyes are full of tears on the fields of their war. This stone shall rise, with all its moss, and speak to other years.”— Ossian.

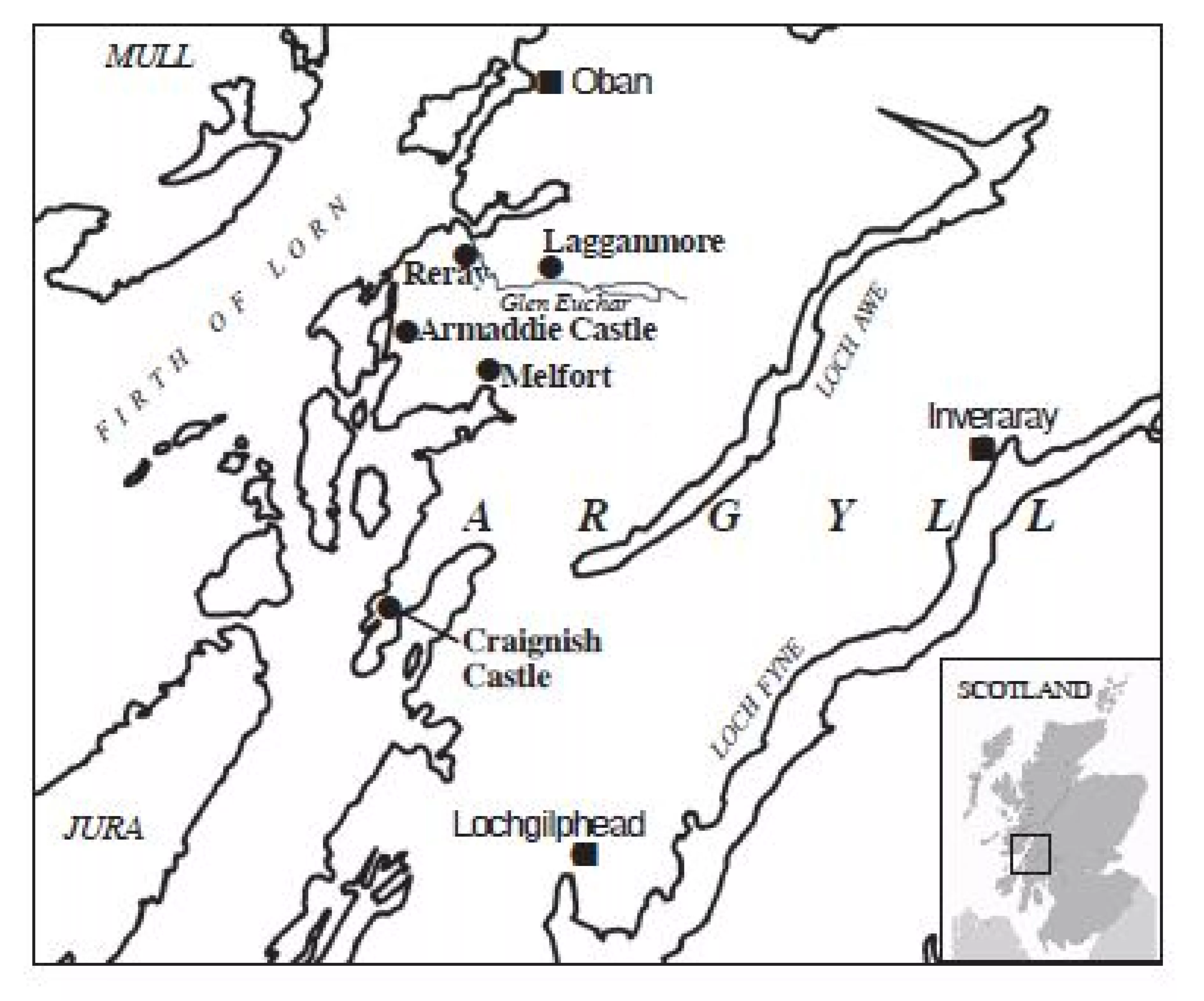

AFTER his futile attempt upon Craignish Castle, (Sir) Alexander MacDonald, in his progress northwards, invaded Melfort. The laird, John Campbell, was absent with his retainers in attendance upon Argyll, and his wife, endeavouring to appease the fierce enemies of her clan, gave orders to have a sumptuous repast laid in the mansion-house, then at Ardinstur, for their entertainment, while she and all the inhabitants hid themselves in the woods and mountain retreats.

The hostile army, having arrived at the house, regaled themselves with the food and drink provided, and being in high good humour, MacDonald issued strict injunctions to his men not to meddle with any of Melfort’s property. Shortly after leaving, and as he ascended the hill to pass over into the neighbouring district of Kilninver, he noticed the house in flames. In a great fury he caused enquiry to be made, and hanged three Irishmen, who were found guilty, upon a gallows erected upon the summit of the hill known as Kenmor, at a place called Tom-a-chrochaidh (the mound of hanging).

Alexander and his army thereafter passed over the hill by a place called Doire nan cliabh (the grove of the Creels)— the mountain track formerly much frequented by wayfarers to and from Easdale roughly indicates the route - and arrived in the evening at the house of Ardmaddie, where the Royalist laird, John Maol MacDougall, resided.

Next day the host of armed men proceeded up a pretty little glen called Glen Risdale, over the ridge bounding Glen Euchar on the south, down Allt Timlich, to Reray House, also a seat of the MacDougalls. Here the army rested to allow stragglers to rejoin. A small body of Campbells, under Ian beag (“little John”) Campbell of Bragleen awaited battle at a place called Laganmor, (Lagganmore) and as Alasdair MacColla’s men moved to the fight, the pipers struck up a war-tune, since known as “Mnathan a’ ghlinne so” ("The Women of This Glen"). The words applied to the composition had a dreadful portent: -

“A’ Mhnathan a’ ghlinne so,

ghlinne so, ghlinne so;

A’ Mhnathan a’ ghlinne so,

‘S mithich dhuibh eiridh”—

...words imploring the women of the fateful glen to arise and fly for their lives. The wail of the tune—it might be called a dirge—was well calculated to inspire the inhabitants with the feeling that desperate work was at hand; but none in that sweetest and most peaceful of glens could conjecture the horrors of the day which had just dawned upon the mountains.

The action between the opposing forces was short, but decisive; the Campbells were hopelessly beaten, and their leader, a man of great strength and courage, was taken prisoner.

Thereafter MacDonald caused his men to scour the glen and its neighbourhood, and drive all the women, children, and old men to the secluded hollow where the fight had taken place. There these inoffensive people, whose only fault was that they belonged to the execrated clan Campbell, were, together with the prisoners, shut up in a large barn, and the building set on fire.

All were consumed, with the exception of the Campbell general, John of Bragleen, who, putting a peat creel on his head, burst through the half-consumed doorway; and a young woman who followed in his wake, and who, being very fleet of foot, quickly out-distanced her pursuers. Her descendants are still in the district.

John of Bragleen was recaptured, and being brought before the Royalist general was asked: What would you do, John, if I was in your place?”

“I would give you a chance for life. Form a wide circle of soldiers around me, and I can break through, let me go,” remarked John.

This was done, but try as he would, he could not manage to break through by force. Having recourse to stratagem, he made as if to force his way, but suddenly throwing his sword high in the air, his opponents, endeavouring to avoid the sword in its flight, allowed John the chance he desired of slipping past.

John Campbell and Alexander MacDonald had many subsequent encounters, but in all their fighting they appear to have had kindly feelings and genuine respect for one another, and in times of strait to have afforded each other what is known as “cothrom na Feinne” (the fair play of the Fingalians).

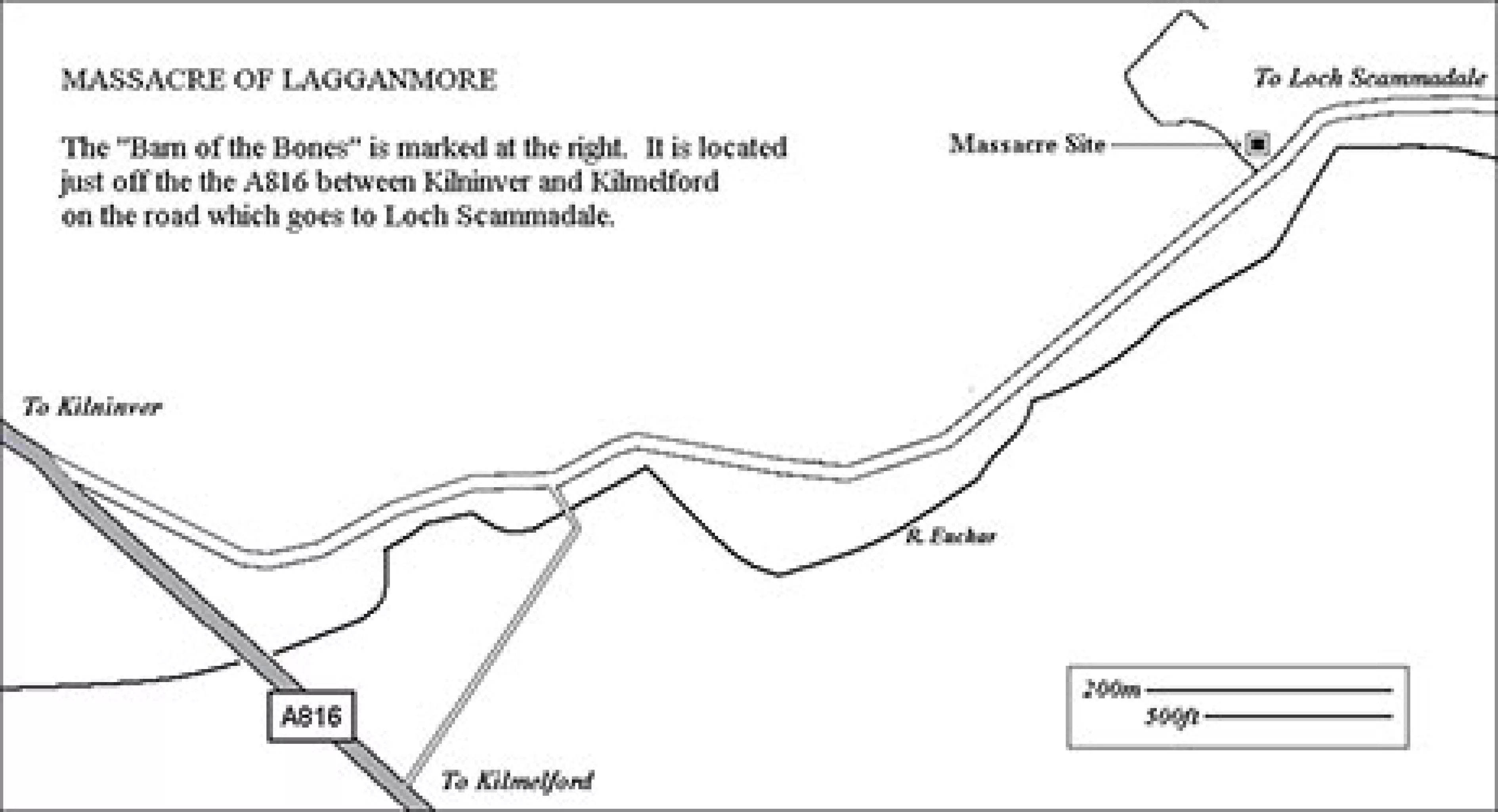

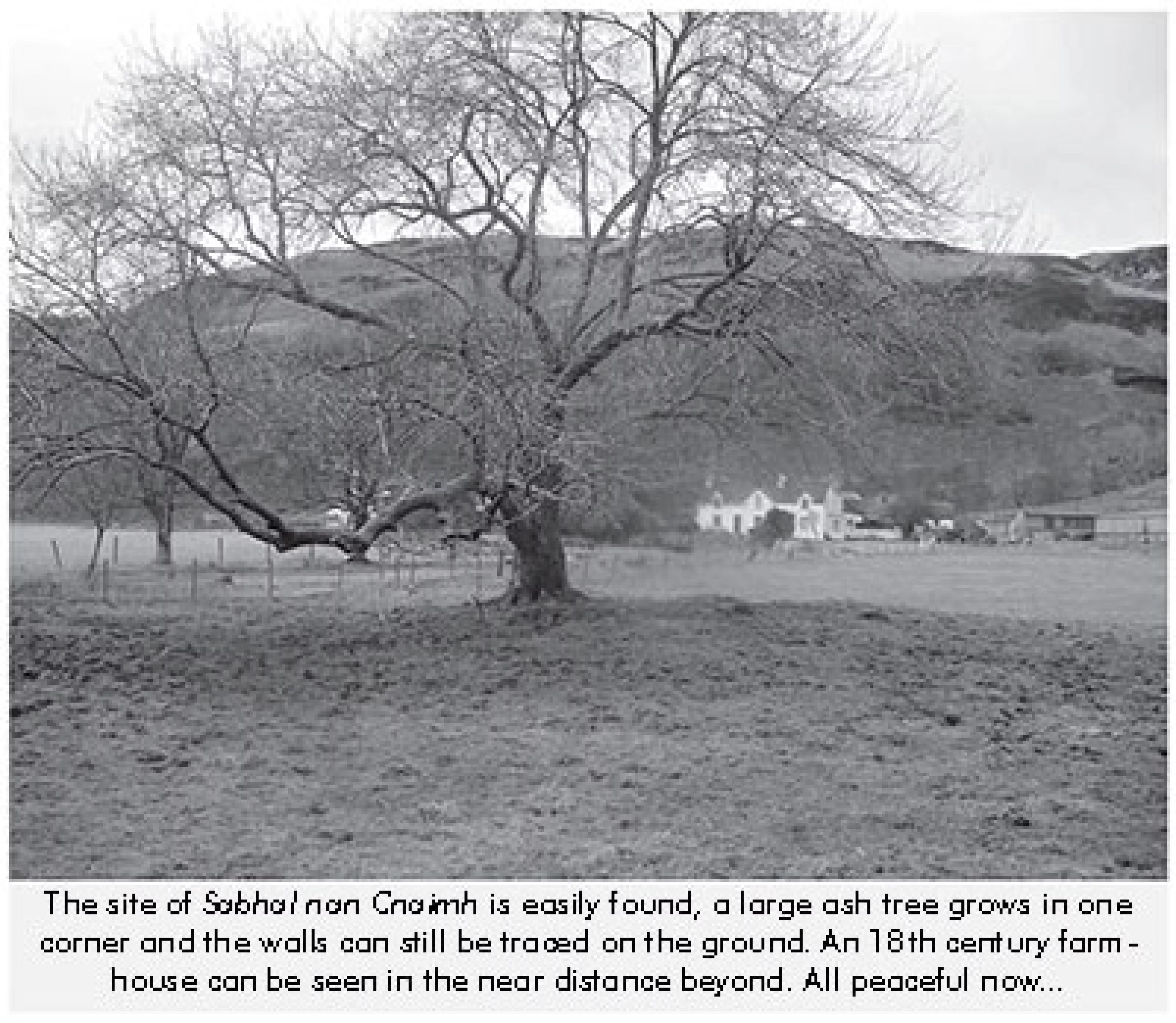

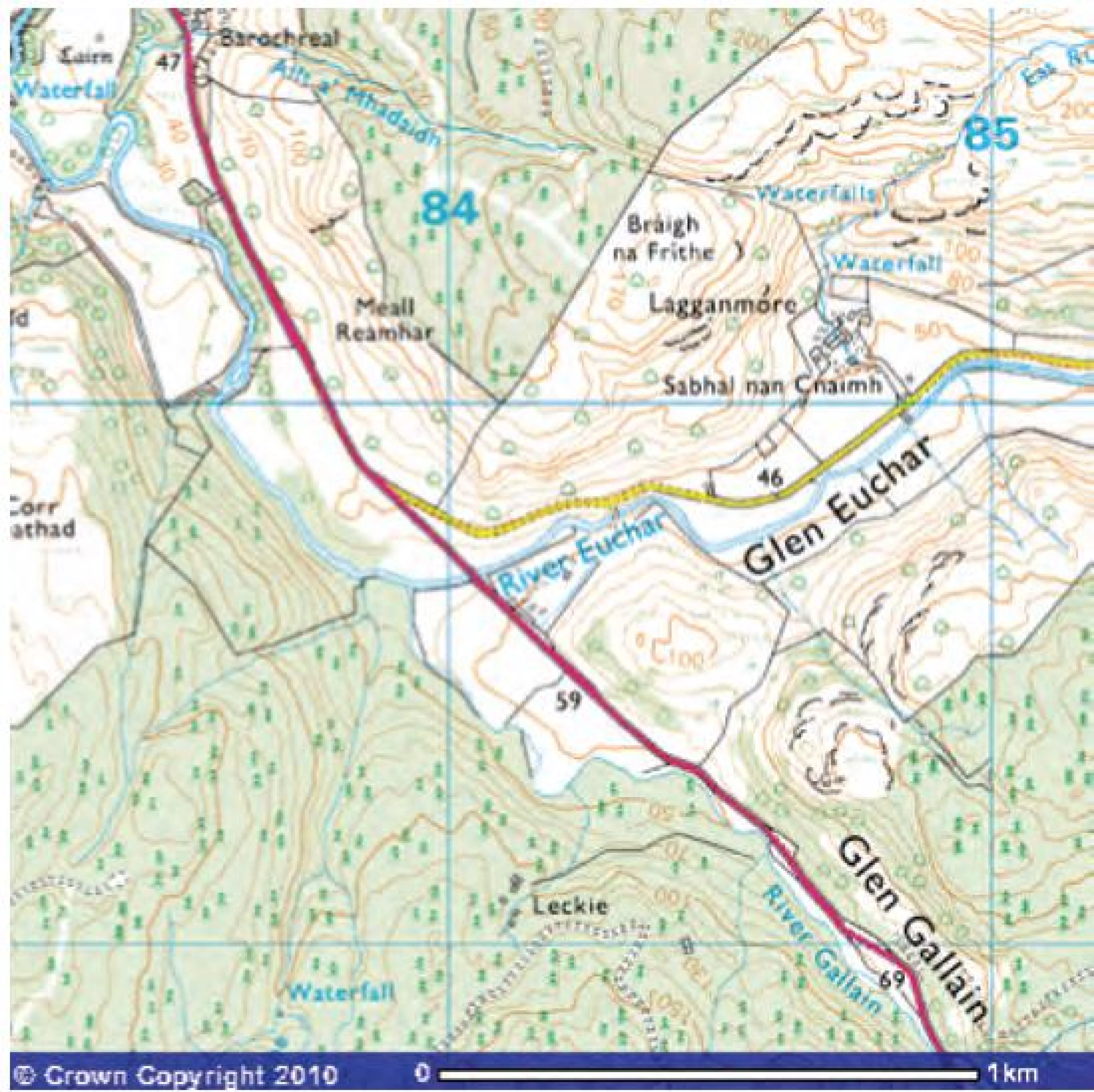

The barn where this massacre was perpetrated is known as Sabhal nan Cnamh (the Barn of the Bones), and a heap of ruins close to the main road at Laganmor in Glen Euchar marks the spot.

The history of Sir Alexander MacDonald is one long record of war and rapine. He was of that branch of the MacDonalds represented by the Antrim family: his father, the notorious Colkitto (Colla ciotach—left-handed Coll), played a prominent part in the wars of the previous half-century, when the Crown’s method of pacification was “garring ane devil dang anither”; his mother was of the Campbells of Achnambreac (Auchinbreck) in Cowal.

MacDonald was a fearless soldier, and a skilful leader of irregular troops. A Celt himself, he thoroughly understood the nature of Highland soldiers, and led them in such a manner as to develop their fighting power to its fullest extent. He may have been no great strategist, and his defence of Kintyre, before the final expulsion of the Royalist troops, was puerile; but his hardships during the previous years, his life of constant danger and excessive exertion, added to an inclination for huge potations of “aqua vitae,” had by that time dulled his intellect, and made him at times more of an unreasoning savage.

+++

Conclusion: Gillies does not give an estimate, but Alastair Campbell of Airds puts the number of men, women, and children burned to death in the Barn of the Bones at over 100. Although the Scottish portion of the civil wars was not clan-on-clan, MacColla’s ravaging of Argyll became MacDonald clan retribution for being on the losing side of history with the Campbells.

In the way of the times return retribution was equally savage, although it was directed against some of the perpetrators of the Lagganmore massacre and did not involve civilian women & children. When Alasdair MacColla left for Ireland in 1647 he left behind many of his followers as garrisons at the castles of Dunaverty in Kintyre and Dunivaig on the island of Islay. After the Dunaverty garrison eventually surrendered to General Leslie’s Covenanter army they were slaughtered man and boy, Irish & Scot, encouraged by the Presbyterian preachers present: for the Argyll men with Leslie, Lagganmore and other atrocities were avenged.

+++

In his essay on “Soldiers and Civilians in the British Isles, c. 1641-1652,” Dr. Frank Tallett, who has a doctorate in history and is the Head of the School of Humanities at University of Reading, Berkshire, England, refers to the Massacre of Lagganmore as an example of the barbarity of war in Scotland during the 1640s, and this edit appears by his kind permission.

“The most powerful of the clans by the first half of the seventeenth century were the Campbells whose lands lay in the Highlands, though they associated themselves with Lowland aspirations... many (Royalists or their allies) thought the real war they were fighting was against the Campbell hegemony."

“...there is no denying the very real cultural, racial, religious and linguistic tensions embittered the fighting between the soldiers and produced atrocities against civilians. One of the best known examples occurred after the battle of Lagganmore. Defeated Campbell soldiers together with women and children from the area were herded into a barn by the victorious troops, many of whom belonged to the rival Donald clan. On the orders of their commander, Alasdair MacColla, the barn was fired."

“Such attacks went beyond mere plundering for the sake of booty. Instead, they involved the deliberate destruction of crops, property and the killing of civilians in a process euphemistically referred to as ‘wasting’...it provided booty, the cement that held the armies together and without which they dissolved. ‘Wasting’ was also a means of destroying a rival’s power. This was the apparent motive behind the attack upon the lands of Campbells…”

Dr. Tallett’s complete essay appears in Warrior’s Dishonour: Barbarity, Morality, and Torture in Modern Warfare, edited by George Kassimeris, published in 2006 by Ashgate Publishing Limited, Hampshire, England, UK.

+++

A Wee Stone in a Big Story,

The Massacres of 17th Century Argyll

By Duncan Beaton, Scottish Contributing Editor, Furnace, Argyll, Scotland

[This article was originally printed in the Journal of the Clan Campbell Society (North America) Vol. 43 No. 3 Summer 2016 and may not be re-published in whole or in part without the written permission of the various authors and the Clan Campbell Society (North America).]

I was reminded of this story when finding a wee pebble in the pocket of a winter jacket worn when it is cold, rather than wet as the winter of 2015-16 has been; consequently the jacket hasn’t been worn much recently. It is also a story covered in Murdo Fraser’s recent book “The Rivals: Montrose and Argyll and the Struggle for Scotland”, which deserves a review on these pages. The story involves the actions of the two great marquises of 17th century Scotland, Montrose and Argyll, how they started out with much in common, their paths diverged until they were bitter enemies, and how they shared similar fates with their heads stuck on a spike at the Edinburgh Tollbooth.

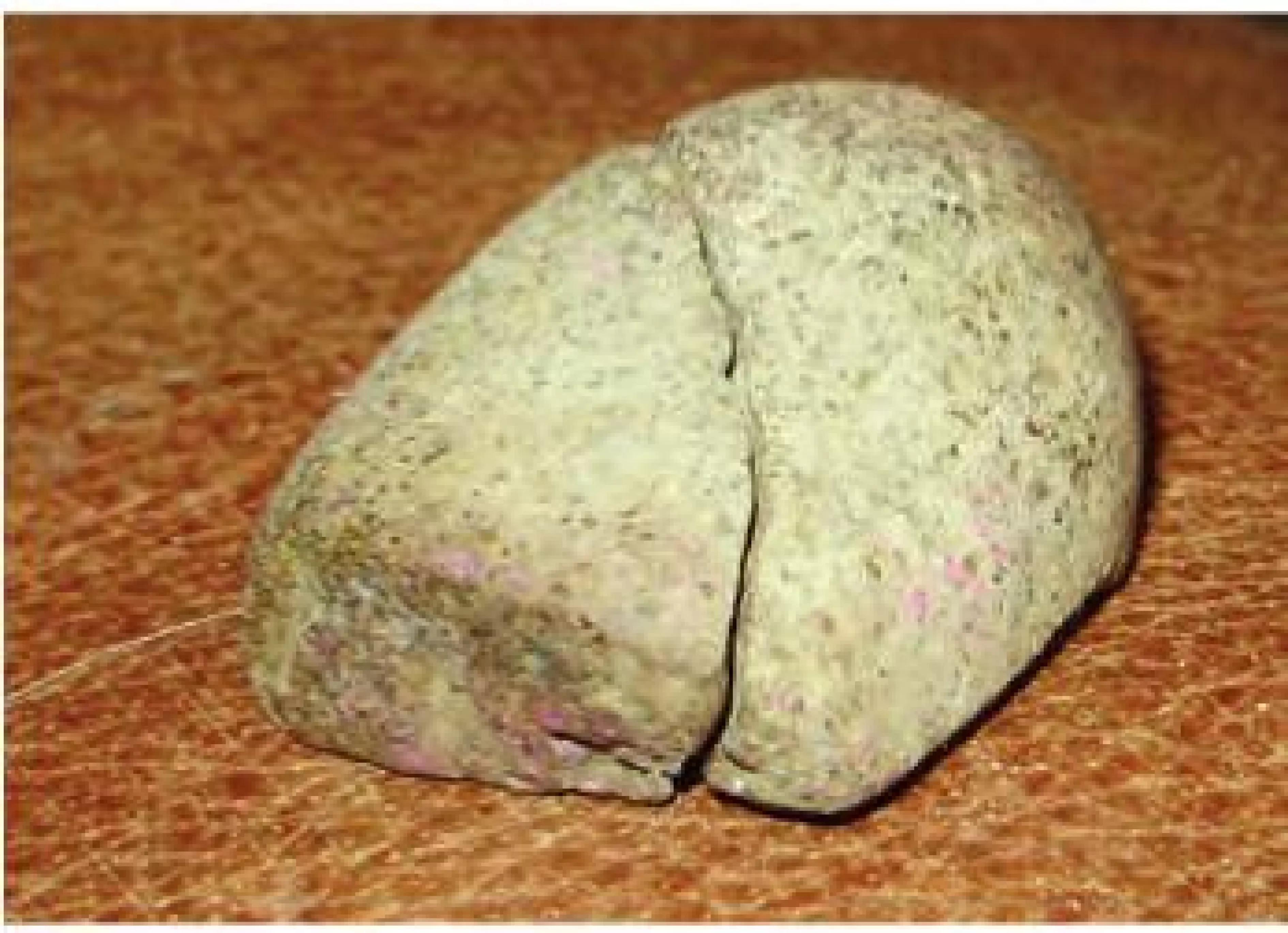

My part in the story started when the editor of this Journal had a story of the massacre at Lagganmore to print, and asked for a photograph of the site. So, on a Spring day before the trees were in leaf, we set off on the Loch Scammadale road through Glen Euchar with camera at the ready. At the Lagganmore Farm road end I jumped over the gate to look at the place where the fateful barn had stood. Scraping the earth with the toe of my boot to expose the foundations, all that survives, this wee stone bounced up and, after a cursory look, I put it in my pocket.

On closer inspection later, I noticed it was badly scorched, and was so brittle that later still it cracked and split in two. Here then was my personal evidence of the horrors that took place in Argyll during “The War of the Three Kingdoms” (Scotland, England, and Ireland), or, as it is more commonly known, the English Civil War.

The background to the civil wars of the 1640s affecting the British Isles is overly complex and has been partly covered in recent articles; sufficient to say here that the involvement of the English Parliament, coupled with the disaffected religious factions in the three kingdoms, would eventually end with the execution of King Charles I and the creation of a Commonwealth presided over by Oliver Cromwell and his victorious Parliamentarian army. Presbyterian Scotland had produced the National Covenant of 1638 against the king’s introduction of an Episcopalian prayer-book. It had been signed by many of the nobility, including Archibald Campbell, later Marquis of Argyll, and copies carried across the country were signed by all classes of the population. The signatories were known as Covenanters.

Events took a serious turn when conflicts arose over loyalty to the king and adherence to the National Covenant. This was too much for some signatories, and choices were made: the Covenant or the King. Covenanter-turned-Royalist James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose, gathered many of the Roman Catholic and Episcopalian Highlanders to fight for Charles, aided by Irish soldiers under Sir Alasdair MacColla, “Alexander, son of Coll”, whose father, the notorious Colkitto (Colla ciotach--left-handed Coll MacDonald), played a prominent part in the little wars of the first half of the 17th century.

The history of Sir Alexander MacDonald (or Alasdair MacColla, as he was known in Argyll) is one long record of war and rapine. He was of that branch of the MacDonalds represented by the Antrim family: the family had taken up residence in Northern Ireland after a marriage with the heiress of Bisset of the Glens, and others had gone there after losing Kintyre to the Campbells in 1607. “MacDonald was a fearless soldier, and a skillful leader of irregular troops. A Celt himself, he thoroughly understood the nature of Highland soldiers, and led them in such a manner as to develop their fighting power to its fullest extent. He may have been no great strategist, and his later defense of Kintyre, before the final expulsion of the Royalist troops, was puerile; but his hardships during the previous years, his life of constant danger and excessive exertion, added to an inclination for huge potations of ‘aqua vitae’, had by that time dulled his intellect, and made him at times more of an unreasoning savage”. (“Netherlorn Argyllshire and its Neighbourhood” by Patrick H. Gillies, M.B., F.S.A. Scot, published 1909).

After initial successes, including the burning of Inveraray in the winter of 1644 and the terrible defeat inflicted on the Campbells at Inverlochy a few months later, when more than 1,500 clansmen were slain, things began to unravel for the Royalist Cause in Scotland. By the time of our story it is 1646, Cromwell is ascendant but not in power yet, Montrose is defeated, the King’s days are numbered. Alasdair MacColla has turned to ravage Argyll.

After a futile attempt on well defended Craignish Castle, MacColla progressed northwards and invaded Melfort. Eventually he arrived in the evening at the house of Ardmaddy, where he and his followers would have been welcomed by the Royalist laird, John MacDougall.

Next day the host proceeded up the pretty little glen called Glen Risdale and over the ridge bounding Glen Euchar on the south, down along the stream to Reray (now on OS maps as Raera) House, also one of the properties of the MacDougalls in Nether Lorn. Here the army rested to allow stragglers to rejoin. A small body of Campbells, under Ian gear (“short John”) Campbell of Bragleen was waiting to do battle at a place called Lagganmore, and as Alasdair MacColla’s men moved to the fight, his pipers no doubt struck up a war-tune.

The action between the opposing forces was short, but decisive; the Campbells were hopelessly beaten, and their leader, a man of great strength and courage, was taken prisoner. Then the mainly Irish troops under MacColla scoured the glen and neighbourhood, rounding up all the women, children, and old men. These inoffensive people, whose only fault was that they belonged to Clan Campbell, were shut up in a large barn with the prisoners, and the building set on fire. Only Ian gear of Bragleen, who put a peat creel (basket) on his head and burst through the half-consumed doorway, and a young woman who followed in his wake, escaped. The barn where this massacre was perpetrated was known long afterwards as Sabhal nan Cnamh (the Barn of the Bones). The site is still marked on the large scale OS (Ordnance Survey) map, and this was where I found my wee stone.

In the way of the times return retribution was equally savage, although it was directed against some of the perpetrators of the Lagganmore massacre and did not involve civilian women & children. The Covenanter army under Lt-General David Leslie was ordered to march to Argyll to deal with Sir Alasdair MacColla MacDonald and his remnant of the Royalist army. At this time the Covenanters were still at Dunblane, north of Stirling and to the east of the country. While there they were joined by James Turner, who served as one of Leslie’s adjutants.

Turner was a son of the minister of Dalkeith Parish and had studied theology at Glasgow University, graduating MA in 1631. However he changed career and became a soldier of fortune in the continental Wars of the Protestant Succession, the same military career path as followed by his new commander David Leslie. He is important in that his is the only eye witness account of what happened next. He was taken prisoner at the Battle of Worcester in 1651, and while in captivity wrote his memoirs.

On the 17th May 1647 the Covenanter army left Dunblane and reached Inveraray on the 21st. May of that year was one of the stormiest and wettest in human memory, so they rested at Inveraray until the 23rd, when they set off for the Kintyre Peninsula where Alasdair MacColla and his troops were known to be lurking. A few days later the two forces met on the level fields at Rhunahaorine Point, just north of the present-day village of Tayinloan. MacColla seemed to have been taken by surprise, and his men scattered in confusion. It was recorded that he lost between 60 and 80 men, with Leslie’s losses nine men.

The Covenanters then kept up a relentless pursuit of their enemies down through Kintyre, reaching Loch-head Kilkerran (now Campbeltown) on the 25th May and taking up residence in quarters recently held by MacColla’s men. However, Sir Alasdair and many of his Irish troops had managed to get away in 15 ships from the harbour, and were shortly afterwards landed in Ireland.

Alasdair MacColla left behind many of his followers as garrisons at the castles of Dunaverty at the south end of Kintyre and Dunivaig on the island of Islay, the latter being under the command of his aged father and his brothers. Between 300 and 500 men, under the command of local laird Archibald mor MacDonald of Sanda and his son Archibald og (“young Archibald”) were left at Dunaverty. General Leslie reached Dunaverty on the 31st May and the siege began.

The castle of Dunaverty was technically at this time a Campbell fortress, being the principal messuage of the lordship of Kintyre which the 7th Earl of Argyll had acquired by Royal Charter after the forfeiture of the MacDonalds in 1607. Built on top of a sandstone outcrop more than 100 feet high with a deep chasm on the landward side, it was well-nigh impregnable. It had been a site of great strength for nearly 1,000 years: the “Annals of Ulster” record that, as Abhairtach (named after an early Celtic tribe), it had been besieged by King Selbach of Dalriada in 714 AD.

The one weakness was the supply of fresh water, drawn from a stream defended by a trench. Leslie knew this, and an assault on the trench was successful: forty of the besieged died in defending it. The main casualty on the Covenanter side was Matthew Campbell of Skipness, who was buried in the old churchyard Loch-head, where his son-in-law the reverend Dugald Darroch was the minister.

There was now no need for further assaults on the castle. Wet and stormy May had given way to warm and sultry June. “Inexorable thirst”, said Turner, made the besieged garrison seek parley.

In Turner’s own words we hear what happened next: “I was ordered to speak with them. Neither could the Lieutenant-General be movd (sic) to grant any other condition then that they should yeeld (sic) on discretion or mercy, and it seemed strange to me to heare (sic) the Lieutenant-General’s nice distinction that they sould (sic) yeeld (sic) themselves to the kingdomes (sic) mercy and not his. At length they did so, and after they were comd (sic) out of the castle they were put to the suord (sic) everie mothers sonne except one young man Mackoull (MacDougall), whose life I begd (sic) to be sent to France with a hundredth countrey (sic) fellows whom we had smoaked (sic) out of a cave as they do foxes, who were given to Captain Campbell, the Chancellor’s brother”.

So the unfortunate prisoners were slaughtered. Did Leslie order the massacre, or merely turn a blind eye to it? Turner continued: “It is true David Leslie hath confessed it afterwards to severalls (sic) and to myselfe in particular oftener than once that he had spared them all if that Nevoy put on by Argile (sic) had not, both by preachings and imprecations instead of prayers, led him to commit that butcherie (sic)”. The implication here is that the reverend John Nevoy, Leslie’s chaplain appointed by his Covenanter leaders under the Marquis of Argyll, had urged the mass killings.

Nevoy was no obscure fanatic, but one of the leading clergymen of the Presbyterian Kirk, the Church of Scotland. Although not all of the Kirk’s leaders of the time were of his ilk, many were, and it was the commonly-held view that all rebels against their version of the Almightly should be exterminated: it was their duty to ensure this was done. To men like Nevoy the Catholic Irish soldiers of MacColla in particular, including the army of women and children who followed them, were “noxious vermin”. After the most recent defeat of the Marquis of Montrose, at Philiphaugh in the Borders, the Irish prisoners and their kin had been separated from the others and executed. This was supported by a resolution passed by the Scots Parliament: “The house ordains the Irish prisoners taken at and after Philiphaugh in all the prisons of Selkirk, Jedburgh, Glasgow, Dumbarton and Perth to be executed without any assise or process, conforming to the treaty between both kingdoms ....” (“Highland Papers”, volume II, p252, Scottish History Society, 1916).

So, is it no surprise that the Dunaverty prisoners should meet the same fate? For the victorious Argyll men present there was also revenge for the atrocities committed by MacColla and his men during the 1644-45 campaign with Montrose, including around Inveraray and Inverlochy, as well as more recent ones such as the burning of the barn at Lagganmore.

However, as with the Lamonts almost exactly a year earlier, it was not only the Irish who suffered: as mentioned earlier MacColla had sought and received support from the MacDougalls in Nether Lorn. That clan had also followed him to Kintyre, but had been left behind at Dunaverty when he fled to Ireland. In the Inveraray Castle Archives there is a document entitled “The Names of the Men who wes murthered at Dounavertie in Kyntyre and Severall Others not to be remembered of in 1646 or 1647”. The list contains the names of 90 men, 49 MacDougalls related in some way to the chiefly and cadet families of the name, and 41 others who bore sept names such as McIlchoan (MacCowan), McKeith, and McMurrich (MacVurich). It is not clear if all died at Dunaverty, or in the campaign leading up to the massacre.

Certainly among those killed were the garrison leader MacDonald of Sanda and his son, who were hanged. Another local Kintyre laird to die was Angus MacEachern of Killellan, an ancient family in that place who had previously been a vassal of the MacDonalds of Islay but who continued to hold his lands from the Marquis of Argyll. Knowing he was to die, he handed a little box full of writs and other documents to James Turner, which he earnestly requested should be delivered to the Marquis “to be preservit for himself and his childrens use”. This Turner did, and on the 21st November 1659 the Marquis disposed of the lands to Colin MacEachern, eldest lawful son of the late Angus.

Today, as at Lagganmore, barely a trace remains of Dunaverty. A small enclosure holds the remains of MacDonald of Sanda and his son, and the bones of others collected later from where they fell. A local tradition says that, as Leslie’s men tired of the bloodshed, many of the prisoners were tied together and thrown from the clifftop to die on the rocks below. With a little imagination, the cries of the nesting sea birds bear testimony to the long, bloody tale of 17th century Argyll.

Appendix - Other sources used:

A History of Clan Campbell volume 2, by Alastair Campbell of Airds.

Memoirs of his Own Life and Times, by Sir James Turner.

Kintyre in the Seventeenth Century, by Andrew McKerral.

+++